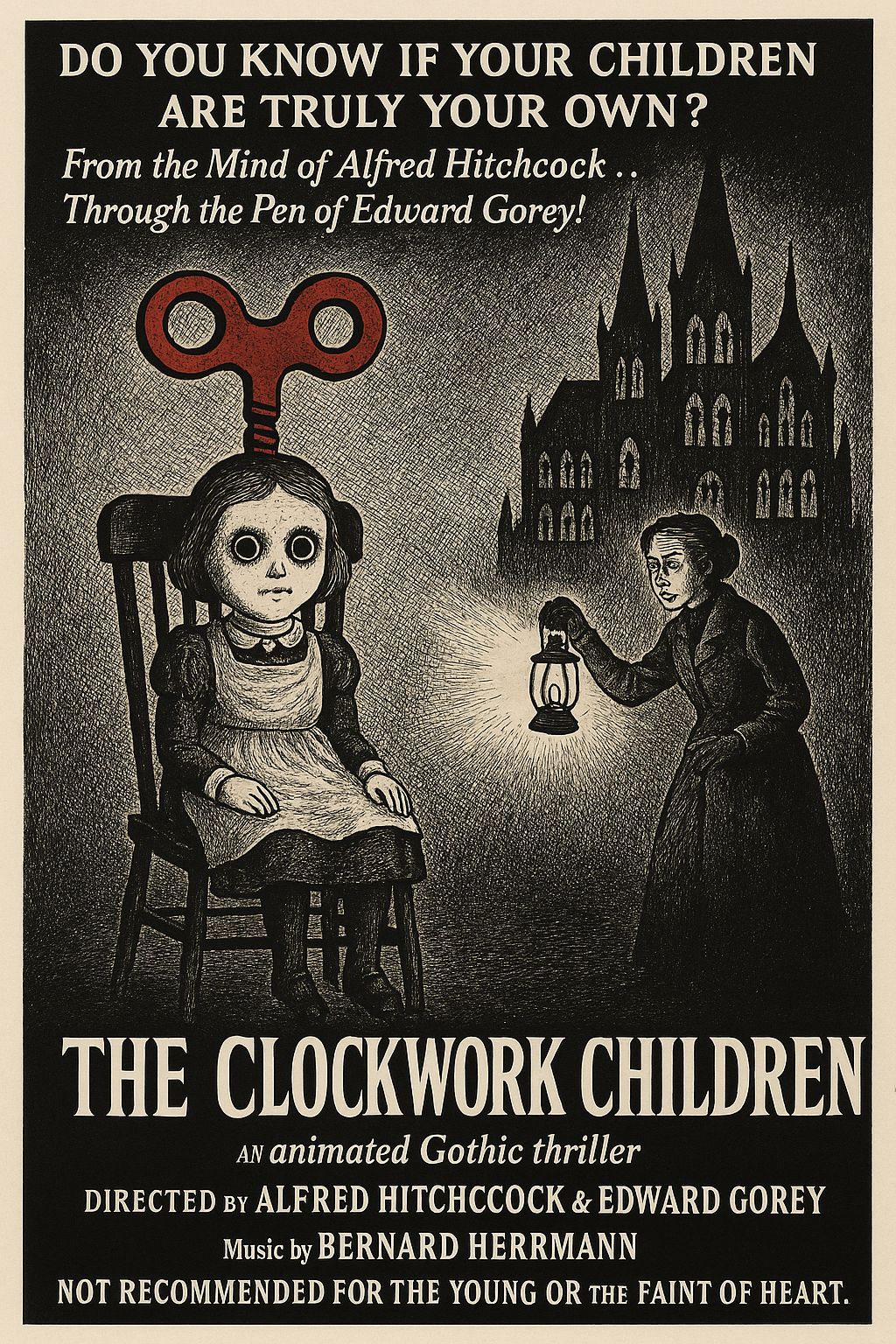

The Clockwork Children (1954) is a chilling animated collaboration between Alfred Hitchcock and Edward Gorey, blending Gothic horror with psychological suspense in a tale of innocence replaced by machinery. Set in a decaying Austro-Hungarian orphanage, the film follows a governess who uncovers a conspiracy to replace real children with mechanical doubles. Combining Gorey’s unsettling visual style with Hitchcock’s mastery of tension, the film is remembered as the first true “animated Gothic thriller.” Though controversial upon release, it later achieved cult status, particularly in Cascadia, and remains a cornerstone of mid-century experimental cinema.

Details of The Clockwork Children

Release Date: October 31, 1954 (United States of New England)

Runtime: 92 minutes

Format: Animated feature in black-and-white, with selective use of muted color tinting (reds and greens) for dramatic effect.

Directors: Alfred Hitchcock & Edward Gorey

Production Studio: Thalia Pictures (New Amsterdam)

Animation Director: Edward Gorey

Story & Screenplay: Alfred Hitchcock, with additional dialogue in rhymed couplets by Gorey

Synopsis

Set in a fog-draped town on the eastern marches of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, The Clockwork Children follows Anna, a governess hired at Saint Aurelia’s Orphanage. At first the institution appears quaint, with rows of pale, silent children seated in Victorian splendor. But Anna notices unsettling details: their eyes blink out of rhythm, their skin smells faintly of oil, and when one scrapes her knee, she leaks something that glitters like mercury.

At night, Anna discovers that real children are abducted and replaced by mechanical doubles. The headmistress insists Anna is suffering from “hysteria,” while local officials dismiss her claims. Only Father János, a disgraced clockmaker-priest, believes her. Together they uncover a conspiracy: the Russian Imperiumis perfecting automaton children as spies, programmed to absorb secrets whispered at bedtime.

The climax arrives during a midnight mass when Anna sees the last remaining human child being dragged beneath the chapel floor. In a desperate chase through crypts and gear-filled chambers, she confronts the Master Engineer—a figure whose face is obscured by a mirrored mask. In the final moments, Anna shatters the Engineer’s control clock, but at the cost of releasing hundreds of half-finished, shrieking automatons into the night.

The film ends ambiguously: Anna escapes into the dawn with one real child, but as the screen fades to black, the rescued child’s laughter begins to tick like a metronome.

Style and Technique

- Gorey’s Visuals: Thin, cross-hatched characters with exaggerated Victorian dress. Sets are detailed etchings of cobblestone streets, decrepit orphanage halls, and candlelit crypts. Gorey insisted on animating dust, moths, and dripping pipes as much as the characters, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere.

- Hitchcock’s Suspense: Long, silent tracking shots of corridors, sudden perspective shifts to the children’s blank eyes, and the infamous “keyhole” sequence, where Anna peers into a dormitory to see children wound up by enormous keys in their spines.

- Sound Design: Eerie use of silence broken by the creak of gears, the hiss of steam, and lullabies sung backward. Composer Bernard Herrmann scored the film with clanging chimes and distorted music boxes.

Reception

- Critical Response (1954): Polarizing. Some critics hailed it as “the first animated Gothic thriller,” while others condemned it as “ghoulishly unfit for children.” Religious authorities in New England denounced the film as an attack on innocence.

- Box Office: Modest initial returns in New Amsterdam and Boston, but it became a sensation in Cascadia after a banned reel was smuggled into Pørtland. Later reissues in Europe, Louisiana and Gran Colombia have developed a cult following.

- Legacy:

- Cited by Cascadian filmmakers of the 1970s as a direct influence on their experimental animation movement.

- Inspired the 1980s horror play Silence at Saint Aurelia’s performed in Wimahl University’s black-box theatre.

- In Russia, where the plot was clearly read as anti-Imperium propaganda, the film was banned until 1991 where it was briefly presented, but then banned again in 1999 with the ascendance of Vladimir Putin as First Consul.

Cultural Impact

- For cinephiles in Cascadia and beyond, The Clockwork Children is remembered as a “lost bridge” between Gothic literature and modern espionage cinema. It hinted at fears of mechanization, surveillance, and the use of children as political pawns—anxieties amplified by real-world tensions between the Russian Imperium and the Empire of Australia.

- In collector circles, original cels from Gorey’s animation fetch astronomical sums. A few are rumored to contain cryptic inscriptions referencing “The Rabbit”, though no consensus exists on whether these were intentional or Gorey’s private jokes.