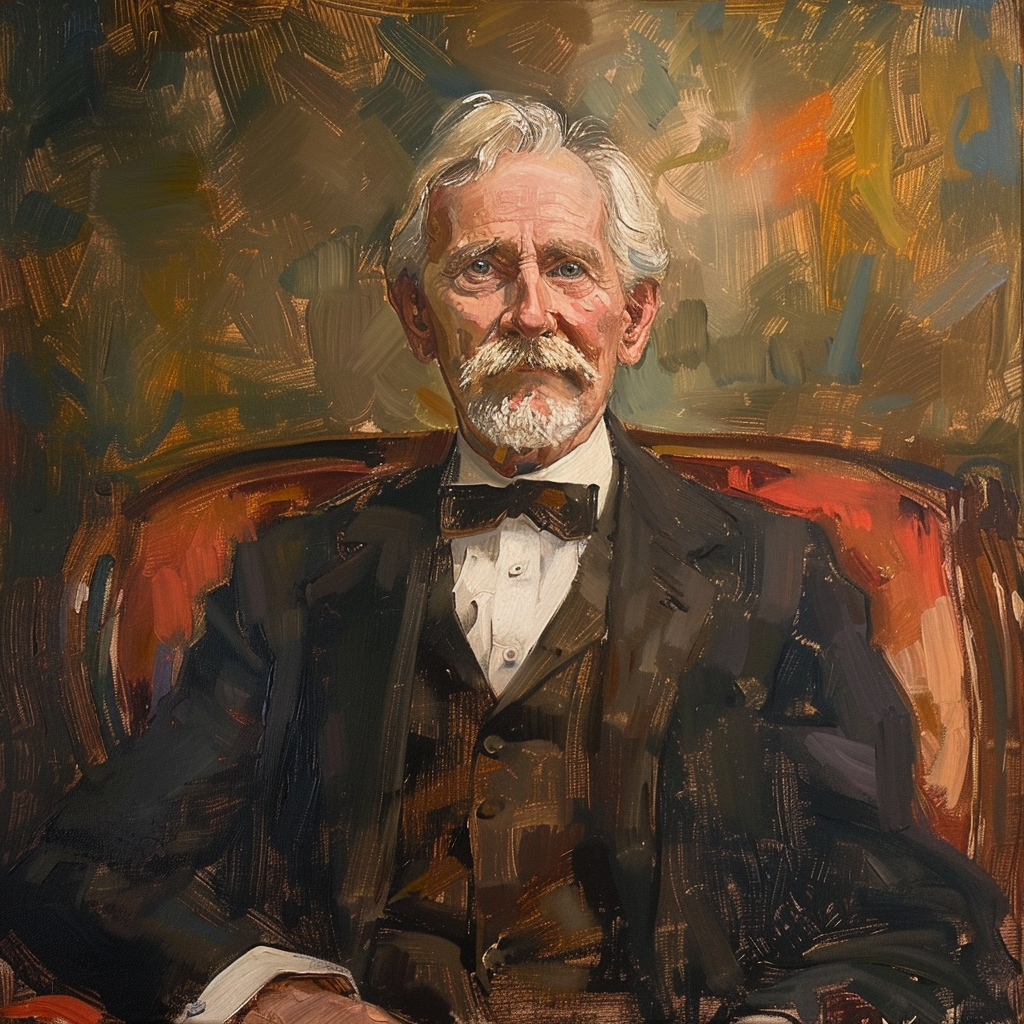

The 10th President of the Union of American States.

The Presidency of Thomas Green Clemson (1850 – 1857)

The Expansionist Tyrant: From Consolidation to Catastrophic Defeat

1850-1855: Clemson’s Internal Consolidation & Militarization

Following the death of John C. Calhoun in late 1850, Thomas Green Clemson ascended to power as the hand-picked heir of the aristocracy. Unlike Calhoun, who ruled with paranoia and purges, Clemson was a calculated, methodical leader, intent on turning the Union into an empire of conquest.

His first years in power focused on solidifying absolute control internally, eliminating any remnants of dissent or instability left from the previous regimes.

Key Actions in the Early Years:

Formalized the Charleston Proclamations, which:

- Officially ended all pretense of elections.

- Declared the Planter Council to be the only ruling authority.

- Further expanded slavery, incorporating new territories acquired through raids and conquest.

Established the Grand Army of the Union, a standing military force under direct aristocratic control.

- Prior to Clemson, most military forces were privately funded militias owned by plantation families.

- The creation of a centralized, professional army allowed Clemson to project power beyond the Union’s borders.

Cracked down on underground resistance movements still operating after Taylor’s assassination.

- Any suspected abolitionist sympathizers, fugitive networks, or nationalist holdouts were hunted down and executed.

- Clemson expanded surveillance programs, ensuring that no internal resistance remained.

Increased industrial output, modernizing weapons production and improving military logistics.

- The Charleston and New Orleans War Manufactories became the largest arms producers in the Union.

- Clemson personally oversaw the development of rail lines, ensuring troops and supplies could move rapidly across the country.

By 1855, Clemson had complete control of the Union, and with his power secure, he turned his attention outward.

1856: The Launch of the Great Plains Conquest

With internal threats eliminated, Clemson and the Planter Council began eyeing the Great Plains as the next step in the Union’s expansion.

Justifications for War:

The Union saw the plains as “lawless” and ripe for conquest.

The aristocracy needed new land for plantations and new populations to enslave.

The Louisiana Compromise, which fixed territorial borders for New England, Louisiana, and Cascadia, left the indigenous lands unprotected, making them vulnerable targets.

Believing that no real resistance would form, Clemson appointed Albert Sidney Johnston as Supreme Commander and authorized a full-scale invasion in 1856.

- The Planter Council assured Clemson that the war would be short and decisive.

- Militias had already been raiding these lands for decades, and there had been little organized resistance in the past.

- Clemson was certain that the native forces were too fragmented to pose a real challenge.

The campaign began in early 1856 with the first major Union offensives crossing the Mississippi River into the Great Plains.

1856-1857: The War of the Seven Nations & Clemson’s Miscalculations

Clemson vastly underestimated the indigenous response.

For the first time in history, the scattered tribes of the Great Plains united under a single war council.

- Sitting Bull and Red Cloud, two brilliant tacticians, formed an unprecedented tribal alliance.

- Envoys were sent to Cascadia, Australia, Louisiana, and New England, warning them that if the Union was not stopped here, they would be next.

- Each of these nations agreed to send military support, recognizing that Union expansion threatened them all.

- Meanwhile, Canada prepared for its own land grab, but was blocked by Australian diplomatic intervention, aided by the Empire of Australia’s spy agency, 1151.

Union Military Failures:

Albert Sidney Johnston was an experienced general, but he had never faced an enemy like this before.

The Union’s forces were heavily reliant on outdated European-style battlefield tactics, making them easy targets for fast-moving indigenous cavalry.

The native warriors used superior mobility and terrain knowledge, striking supply lines and ambushing Union forces in unexpected locations.

Union forces, accustomed to quick plantation raids, were unprepared for a prolonged war.

Despite superior weaponry and resources, the Union suffered defeat after defeat.

By mid-1857, the entire campaign had collapsed.

1857: The Total Defeat & the Birth of the Sioux Nation

By late 1857, the Union forces were in full retreat.

- Albert Sidney Johnston, desperate to salvage the war, launched a last-ditch counteroffensive, but his army was surrounded and destroyed.

- The remaining Union forces fled back across the Mississippi River, abandoning all conquests.

- Clemson, enraged by the defeat, ordered mass executions of generals and officers he deemed incompetent.

But the war’s consequences extended beyond just the battlefield.

The indigenous alliance, victorious for the first time, declared the creation of the Sioux Nation.

The Sioux Nation became a recognized sovereign entity, controlling the Great Plains.

Cascadia, Australia, Louisiana, and New England signed treaties recognizing the Sioux Nation’s independence.

The Union was humiliated, forced to abandon its expansionist ambitions—at least for now.

For Clemson, this was the first major failure of his regime—a stain on his legacy that he would never forget.

The Final Years of Thomas Green Clemson (1857-1888): The Long Decline

From Military Defeat to Economic Expansion & the Deepening of the Slave Economy

1857-1865: Post-War Reorganization & Suppression of Dissent

Following the catastrophic defeat in the War of the Seven Nations, Clemson turned inward, focusing on consolidating control and rebuilding the Union’s strength.

- Clemson blamed the Union’s failure on disloyalty within the military, leading to mass executions of officers and generals.

- The Grand Army of the Union was reorganized, prioritizing political loyalty over competence.

- All discussion of the war was outlawed. Any public criticisms were met with imprisonment or execution.

- Interstate travel restrictions were imposed, preventing laborers from fleeing westward into free territories.

- The Union’s borders along the Mississippi River became heavily fortified, preventing any future incursions from foreign powers.

Though the Union was no longer capable of territorial expansion, Clemson ensured that it remained a highly militarized state.

1865-1870: Economic Expansion, Industrialization & the Deepening of the Slave Economy

With military conquest off the table, Clemson shifted focus to economic strength, expanding industrial infrastructure while intensifying the exploitation of enslaved labor.

- The Union’s economy became entirely dependent on enslaved and indentured labor.

- Massive industrial plantations were established, combining factory-based production with traditional agriculture.

- Rail networks expanded, linking Jacksonville, Havana, Charleston, and Richmond to facilitate the rapid transport of enslaved laborers and plantation goods.

- As the domestic enslaved population proved insufficient, Clemson’s government escalated global slave-hunting operations.

To meet the growing demand for labor:

- Kidnapping of free people from underdeveloped nations became a state-sanctioned practice.

- Victims were taken from India, China, and various African kingdoms, but no part of the world was truly safe from Union slavers.

- The Union’s policy was simple: anyone unprotected by a strong navy, army or diplomatic influence was a potential target.

- A long-term partnership was forged with the Aro Confederacy in Africa, which supplied enslaved people to the Union until the 1970s.

- Forced breeding of enslaved populations was enshrined in law.

- The state officially encouraged the mass rape and forced pregnancy of enslaved women, viewing it as a cost-effective way to “increase property.”

- Laws were enacted to provide tax incentives for plantations that “self-produced” new laborers.

- The Great Slave Market in Charleston expanded, becoming the largest in the world.

- Additional slave markets flourished in Havana and the Aro Confederacy, ensuring a steady flow of new captives.

These policies ensured continued economic growth but deepened the Union’s isolation on the world stage. While New England, Louisiana, Cascadia, and Australia had banned the slave trade outright, the Union’s refusal to do so only solidified its status as a rogue state.

1870-1880: The Shadow Wars & the Struggle for Influence

Though Clemson could no longer expand militarily, he turned to covert operations to maintain the Union’s influence.

- Union agents infiltrated New England and Louisiana, funding dissident factions to weaken their governments.

- Slave traders, smugglers, and privateers established black market trade routes, allowing the Union to bypass economic embargoes and continue exporting plantation goods.

- Espionage became a key tool of statecraft, with Clemson overseeing the development of an early intelligence apparatus.

During this period, Clemson’s government maintained influence through subterfuge rather than direct conquest, ensuring that the Union’s economy remained functional despite international condemnation.

1880-1888: The Twilight of Clemson’s Rule

As Clemson aged, his once unchallenged rule began to face resistance—from the aristocracy itself.

- By the early 1880s, Clemson’s health deteriorated, and he became increasingly paranoid about disloyalty.

- The Planter Council, once fully loyal to him, began to fracture, with some members criticizing his economic policies and inability to reclaim lost territories.

- Rivalries among aristocrats grew more violent, with Clemson’s closest advisors maneuvering for power in anticipation of his death.

- Despite the cracks in his rule, Clemson refused to step down, remaining a reclusive and increasingly erratic figure.

- In 1888, Clemson died.

Legacy of Clemson’s Rule (1850-1888)

- Expanded and industrialized the Union’s slave economy, increasing its dependence on human trafficking, forced breeding, and foreign slave markets.

- Suffered the Union’s first major military defeat in the War of the Seven Nations (1856-1857), forcing a pivot to economic and covert warfare strategies.

- Established espionage and black-market trade networks, allowing the Union to survive despite growing international condemnation.

- Left behind a fractured aristocracy, with his death in 1888 triggering internal power struggles.

Clemson’s rule transformed the Union into a hyper-militarized, slave-driven economy, but his inability to expand its borders left the aristocracy discontent and the Union vulnerable. His death set the stage for a new era of internal conflict and external pressure.