The second President of the Union of American States.

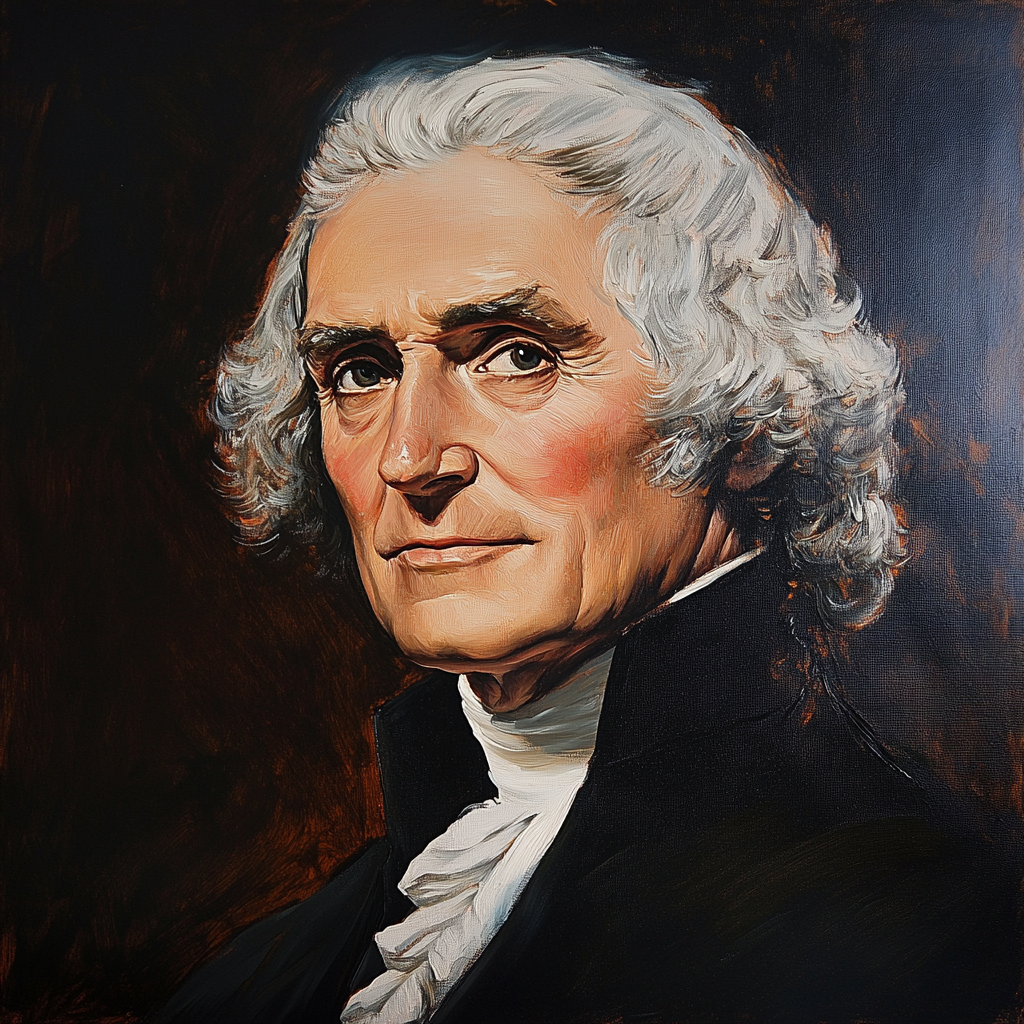

The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1799 – 1809)

The Rise of the Planter Elite and the Expansion of Slavery

1799: Jefferson’s Election & the Shift Toward Aristocratic Rule

Thomas Jefferson, a staunch advocate for states’ rights, plantation economics, and expansionist policies, was elected in 1799, succeeding George Washington. His presidency marked a significant shift in the power structure of the Union, as Jefferson aligned himself almost entirely with the planter aristocracy—a move that would define his rule and push the Union closer toward authoritarianism.

While Jefferson publicly championed democracy and liberty, his administration worked to solidify the dominance of the plantation class, ensuring that all key economic and political power remained in the hands of a small elite.

- He opposed any federal regulation of slavery, declaring it a state issue that the national government had no right to interfere with.

- He dismantled many of Washington’s centralizing policies, giving more autonomy to individual states—which, in practice, allowed powerful landowners to rule unchecked.

- He expanded westward aggressively, pushing further into indigenous lands and strengthening the Union’s hold over Florida, Georgia, and Alabama.

Jefferson’s election marked the beginning of a clear power shift away from the remnants of Federalism and toward a government run entirely in the interests of the plantation class.

1801-1803: The Slavery Expansion Acts

One of Jefferson’s first major moves was to pass the Slavery Expansion Acts (1801-1803), a series of laws that:

- Encouraged the forced migration of enslaved people to new territories, ensuring that slavery became entrenched across the entire Union.

- Created tax incentives for plantation owners to purchase more land and expand their labor force.

- Weakened manumission laws, making it significantly harder for enslaved people to be freed.

Jefferson personally oversaw the massive growth of the Charleston Slave Market, turning it into one of the largest hubs of the global slave trade. His administration actively worked with human traffickers, importing enslaved individuals from Africa and forcibly relocating others from the Caribbean.

1804-1805: The Louisiana Crisis & Near War with New England

Jefferson’s expansionist ambitions brought him into direct conflict with both Louisiana and the United States of New England.

- 1804: The Union attempted to seize control of the Mississippi River trade routes, claiming that Louisiana’s trade agreements with New England were harming Union interests.

- This led to a near-war with New England, which threatened military action if the Union tried to blockade or seize Louisiana.

- Jefferson ultimately backed down, but the conflict led to a deepening rivalry between the two American nations and increased militarization on both sides.

1806-1807: The Underground Exodus Begins

As the Union became increasingly hostile toward abolitionists and free Black communities, secret networks began forming to smuggle people out of the country.

- The first escape routes to Louisiana and New England were created in 1806, aided by sympathizers in border towns.

- The movement grew steadily throughout Jefferson’s presidency, laying the foundation for what would later become the extensive underground escape networks of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Jefferson’s response was brutal:

- He passed the Anti-Subversion Act (1807), which made it illegal to aid or harbor fugitive enslaved people.

- He empowered private militias to hunt down escapees, leading to violent raids on abolitionist communities in the Union.

1808-1809: Jefferson’s Final Years & The Rise of the Calhounist Movement

By the end of his presidency, Jefferson had successfully expanded the power of the plantation class, but at the cost of increasing unrest and instability.

- A growing movement of young radicals, led by figures such as John C. Calhoun, pushed for an even more extreme aristocratic government—one that would abolish elections entirely and place control directly in the hands of the wealthiest landowners.

- Jefferson did not openly endorse these ideas, but he laid the groundwork for what would later become the Calhounist movement by ensuring that the planter elite held all real power.

In 1809, Jefferson declined to run for a third term, retiring as a revered figure among the aristocracy. His successor, James Madison, would inherit a nation that was already drifting toward oligarchy.

Legacy of Thomas Jefferson’s Presidency

- Solidified the planter aristocracy’s control over the Union.

- Expanded slavery, ensuring its dominance in the economy.

- Strengthened the Charleston Slave Market, making the Union a major hub of the global slave trade.

- Nearly went to war with New England over Louisiana, intensifying rivalries between the two nations.

- Sparked the first organized escape networks, leading to future resistance movements.

- Created the political conditions for the rise of the Calhounist movement.

Jefferson is remembered as one of the most influential presidents of the early Union era—a visionary to the aristocracy, but a tyrant to those who sought freedom. His policies ensured that slavery would remain entrenched for generations and paved the way for the authoritarian governments that followed.